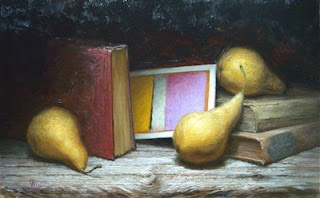

In this post I'll walk through the making of a still life painting called "Purple Palimpsest". Click on the photos below to see larger close-ups. This still life process is a combination of 17th / 19th century techniques and is inspired by contemporary painters such as Jacob Collins and Kate Lehman. The use of a multi-step "indirect" painting process allows the artist to focus attention on executing one aspect of the painting at a time, isolating rather than juggling the many complicated variables such as drawing, composition, application, hue, value and chroma.

The Concept

In this still life painting I'm arranging pears, books and a postcard of a favorite Mark Rothko painting in a geometric configuration, with the postcard setting the overall color scheme. The center of interest occurs at the intersection of the fully lit postcard and the principal pear. The concept behind this piece is to create a visual vocabulary that will hopefully communicate the following things:

- On a narrative level, make an art historical statement that tries to integrate the legacy of modernism with the recent resurgence in 19th century-style realism.

- On a visual level, explore the relationship between abstraction and representation by "re-contextualizing" an image of an abstract painting through the device of executing the image in a traditional format.

- On a symbolic and philosophical level, explore the relationship between the intellect (represented by the sparse geometry of the Rothko postcard and the books) and the sensual world (represented by the anthropomorphic pears and the driftwood board), and examine how the two can be integrated in a harmonious, balanced, and beautiful way.

The Setup

The SetupVarious configurations of the still life objects are tried, with small charcoal sketches made in order to test out the composition. After several iterations, a final setup is selected based on the charcoal compositional sketches. The setup is done under a natural north light skylight with black felt creating a "box" around the objects to control lighting and obtain a chiaroscuro effect of forms emerging out of the dark, after the example of a 17th century Caravaggio or Zurbaran painting.

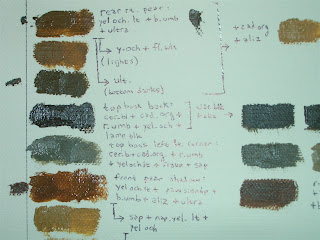

The Poster Study

In order to arrive at a final color scheme, small studies are made in oil, massing in the average hue/ value/ chroma of each large shape in a "posterized" version of the painting. The sketch is made working from dark to light, painting each shape side by side rather than jumping around, so that comparisons can be made and each brushstroke can be judged for temperature ("is it too warm or too cool?") and value ("is to too dark or too light?"). Successful color combinations are saved as swatches on a piece of canvas and labeled for reference with the colors that were used. This swatch sheet becomes the basic reference palette of the painting and is used to mix the major strings when the final painting begins.

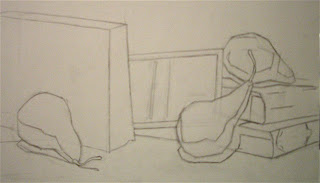

Drawing:

A graphite line drawing is done from life in order to ensure simple, organic, harmonious relationships between the large shapes and sweeping lines of action. Proportions are established through comparative measurement and viewing the drawing in sight-size to identify proportional errors and speed up the drawing process. Photography is not used because it can result in a flat, "cut-out" looking drawing and is subject to the "fish-eye" distortions of lens curvature. The drawing consists of an "envelope" or "block-in" of the objects with the separation between light and shadow (the "terminator" line) indicated. No modeling is done in the drawing, and only the broad sweeping line movements are indicated. The drawing is kept at a simple "blocky" stage so that there will not be a temptation to "tighten up" during the painting process in order to avoid losing small drawing details.

Transfer

TransferThe drawing is then transferred to a sanded birch board that has been primed with Gambiln's white oil ground in a succession of thin coats, and then covered with an imprimatura ground layer of raw umber that has been thinned with odorless mineral spirits. The transfer is done by tracing the drawing onto tracing paper, covering the back of the tracing paper with raw umber oil paint, placing the tracing paper face-up on the painting surface and going over the lines with a ball point pen to make an impression through to the painted side of the paper.

Open Grisaille

Once transferred, an "open grisaille", (also called a "wipe out" or "imprimatura") is painted using raw umber for the darks and the white of the board for the lights. (This as opposed to a "closed" grisaille which uses white paint for the lights). The advantage of the "open" grisaille is that the reflective surface of the board shows through, and creates an effect of glazed luminosity when light is shown on the painting and it reflects back to the viewer through all of the paint layers.

The open grisaille establishes a crude value structure, locks in the drawing using paint, and leaves loose edges if large bristle brushes are used. The transparent raw umber creates atmospheric effect which will show through in the dark areas of the final painting. The raw umber is applied with large bristle brushes and the light areas are created by scraping away the paint to reveal the white board surface. Thinner is used as needed to cut through the paint and expose the white ground of the board. It is very helpful to use bristle brushes that have been cut down to create a scraping tool that will etch through the paint.

Ébauche or First Pass:

The first pass consists of a thinned layer of paint which is mixed to a slightly darker, less chromatic "average" color for each major plane visible in the objects. This creates a baseline "context" of color against which subsequent brushstrokes can be judged. By mixing a lower contrast, dull or "dead" palette, there is plenty of room or "range" left to add chroma and value in later stages of the painting.

Strings of paint (ranging in value from the darkest to the lightest visible) are mixed based on the poster study swatches. Each form is simplified into its major planes, as if they are the facets on a disco ball. Paint is applied by "crawling" out across the form, from the shadows towards the light-facing planes. At this stage, the major plane boundaries are delineated in a "choppy" geometric look, not blended together. This will make it easier to identify and correct drawing and value problems at this early stage.

Modeling:

After the first pass has dried, the subsequent passes can be made with the brushes dipped into a "fatter" medium of 2/3 stand oil, 1/3 thinner so that they will sit on top of earlier passes and leave them intact. Once again, paint is applied by crawling out across the form, from the shadows towards the light-facing planes, frequently stepping back from the canvas and squinting to compare the large temperature and value qualities of the painting with life. This is where the bulk of the real painting happens.

The setup is used as a reference for the movement of form and is not necessarily "copied", as artistic decisions are made, consistent with the desire to create a "convincing" illusion of form and space which will create a more arresting dialogue with the viewer. The setup at this point is being used as a "reference", since the ebauche phase has already established overall value and temperature relationships that are analogous to the relationships that exist in nature.

In order to avoid an "overworked" feeling, each brushtroke is placed deliberately and corrected with a subsequent color rather than by smearing or blending in an attempt to turn form with an airbrushy effect. The shape and placement of each brushstroke should further correct and refine the drawing, and create the desired edges as one stroke is dragged over the next in an overlapping "tile" effect. The temptation to touch the surface more than once with each loaded brushstroke to massage or smear the paint is avoided, as this results in muddy color and murky atmosphere. If each stroke is left intact and corrected with subsequent strokes, the paint application will retain "freshness."

While progressing around the forms, the puddles of paint are adjusted warmer or cooler to make them recede or come forward in space. High contrast and high chroma is used selectively to make forms advance in space and create a center of interest. Edges are adjusted to make objects recede using softer edges, or come forward using harder edges and more contrast.

Usually 2 or 3 complete modeling passes are required and the centers of interest are resolved and developed further than the other areas of the painting. Before each subsequent pass, the painting is "oiled out" by rubbing in the medium gently with a fan brush to bring out the luster and true color.

Finishing:

The highlights are built up with thicker, more chromatic paint. The temptation to use white is avoided as this results in a "chalky" or washed-out look. The center of interest is resolved with additional detail while less important areas are left undeveloped and may remain untouched since the ebauche phase. Paint fattened with medium may be applied as a glaze to simulate surface effects, create translucency or to modify the temperature of a previous layer. Finally, the painting will be oiled out to unify the finish and may be varnished after drying for a year. A frame is selected to compliment the aesthetic of the painting rather than the environment in which the painting will temporarily be displayed.